Documentary: Becoming Helen Keller

Helen Keller has become a beacon for anyone interested in making a lasting contribution to the world. American Masters, an award-winning signature PBS series, captures that sentiment with their documentary Becoming Helen Keller. This film reveals little-known details of Keller’s personal life and examines her public persona and advocacy, including the progressive reforms she helped achieve.

In the film, actor, and dancer Alexandria Wailes provides American Sign Language interpretation of Keller’s words with other ASL interpretations by writer and rapper Warren “WAWA” Snipe. Narrated by author, psychotherapist, and disability rights advocate Rebecca Alexander, the film also features on-camera performances from Tony- and Emmy Award-winning actor Cherry Jones reading Keller’s writings. Additionally, the program has an audio description by National Captioning Institute and closed captioning by VITAC.

I appreciate the documentary because it explores Keller’s characteristics as a prominent leader, away from the standard narrative regarding her loss of hearing and sight. Textbooks often memorialize her as a child symbol of perseverance but seldom follow Keller’s story into adulthood. Reflecting on what I’d learned about her, it turns out my knowledge was minimal.

Helen Keller, 1907 Credit: Courtesy of Library of Congress

The Word Water

At age two, Keller became both deaf and blind due to illness. Although Keller’s mother believed her daughter should have an education, few options existed. Her parents adopted “home signs,” or basic gestures for food, sleep, and other life necessities to communicate with the young girl. Then a woman named Annie Sullivan was assigned to the Keller’s home to teach the young girl. Sullivan helped Keller make tremendous progress with her ability to communicate.

In one dramatic struggle, memorialized by Keller’s autobiography The Story of My Life and the play/film The Miracle Worker, Sullivan taught Keller the word “water.” She helped Keller connect the object and the letters by taking Keller out to the water pump and placing Keller’s hand under the spout. While Sullivan moved the lever to flush cool water over the girl’s hand, she spelled out the word w-a-t-e-r on Keller’s other hand.

Keller understood and repeated the word in Sullivan’s hand. She then pounded the ground, demanding to know its “letter name.” Sullivan followed her, spelling out the word into her hand. Keller moved to other objects with Sullivan in tow. By nightfall, she had learned 30 words.

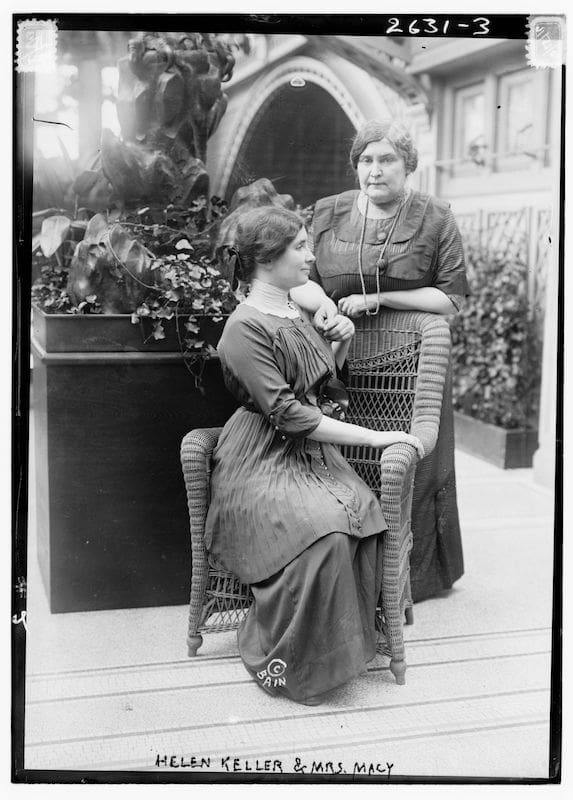

Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan, 1913 Credit: Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Becoming a Writer

Keller learned to read-write and also discovered it was possible to understand what others were saying by placing her hands on faces to feel the vibrations of spoken words. She went to Perkins School for the Blind, the same school Sullivan had attended, and received assistance from famed inventor Alexander Graham Bell.

In school, Helen wrote her first original story. Unfortunately, the school headmaster accused her of plagiarism. Although deeply wounded, Keller continued to write, but the incident caused her to leave Perkins. At age 12, one of her stories caught the attention of Mark Twain. He formally put together a scholarship for Keller, who eventually attended Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

There was controversy because then it was unusual for women to attend college, much less one who was blind and deaf. Keller had to rely on friends to convert her exams to braille, and she received no special accommodations. At Radcliffe, Keller published articles, which became the book Story of My Life, and graduated college with honors. Her second book, The World I Live In, focused on touch’s role in Keller’s world.

The Activist

After working together for years, Keller and Sullivan became activists. For Keller, this meant focusing her attention on the poor and disabled. She became a suffragist, pacifist, socialist (Keller was a member of the Socialist Party of America and the labor union Industrial Workers of the World ) and supported birth control. Keller and Sullivan traveled across the country, speaking publicly to large audiences.

Keller would also pen a letter of support for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and made a monetary contribution to the organization. In 1920, she helped found the American Civil Liberties Union. Keller consistently spoke out against the United State’s involvement in wars. She was also drawn into the public debate about eugenics and expressed concern about human overpopulation.

In 1924, Keller became an ambassador for the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB). For the next 44 years, she toured the United States, developing support for programs that assisted blind people. One caveat, Keller was not to discuss her political views. During her time with AFB, she did persuade President Herbert Hoover to host blind leaders and standardize braille in schools. She also pushed for libraries and schools to have access to braille.

After Sullivan passed away in 1936, Keller continued to travel with companion Polly Thomson and write. Altogether she wrote twelve published books and several articles. During World War II, she visited with soldiers who had become disabled due to war injuries. After the war, Keller would travel to Japan, securing her position as an influential American ambassador that traveled the world. Keller’s last speech took place in 1961, where she advocated for more special education funding. She died in 1968.

Helen Keller with Eleanor Roosevelt, 1936 Credit: Courtesy of Library of Congress

Later Chapters

Becoming Helen Keller shows an extremely complex woman with conflicting dimensions. Many disabled people have conveyed that the saintly younger image of Keller falls ridiculously short of understanding her as a historical figure. She is a powerful American tale, and future generations need to explore her later life chapters as much as the earlier ones.

Becoming Helen Keller

American Masters

Website

Now streaming on PBS Passport, Apple TV, Amazon, and Comcast.

Written by Nadia Syed

Trailer provided by American Masters

Images provided by the Library of Congress

More Girls That Create Posts

Beyond the CANVAS Features Inspirational Women Creators